Moderatori/ce: F1NAC,Zweki,Scuderia,Cuky,47,gringo73,luka_kimi

Prognoza za Maleziju je isto bila kisa, tak da ne mora znaciti da bude kise. Ali nadam se suhome pocetku i onda kisiIgor18 je napisao/la:Prognoza vremena za Shangai

Ako "smo" jučer izbjegli kišu, vjerujući ovoj prognozi u kini nas očekuje kišni vikend.

prosječno 31 u trciDani je napisao/la:Pa kolike su temperature bile?

28 zraka, 31 staze (na početku utrke).Dani je napisao/la:Pa kolike su temperature bile?

I još treba uzet u obzir to koliko je u Kini dug onaj pravac prije startno ciljne, i bez DRSa tamo svake godine bude svačega (predpostavljam da će zona korištenja biti upravo ta ravnina).Armanini je napisao/la: nadam se da ce ovdje taj vrag vrag od drsa doc do punog izrazaja i da ce prednost bit ogromna i prevelika pa da odluce da se ne koristi vise

Sigurno će ta ravnina biti zona korištenja ali neće valjda od početka ravnine biti dozvoljeno, to mi se čini malo previše jer taj pravac je izuzetno dugačak.ice_man je napisao/la:I još treba uzet u obzir to koliko je u Kini dug onaj pravac prije startno ciljne, i bez DRSa tamo svake godine bude svačega (predpostavljam da će zona korištenja biti upravo ta ravnina).Armanini je napisao/la: nadam se da ce ovdje taj vrag vrag od drsa doc do punog izrazaja i da ce prednost bit ogromna i prevelika pa da odluce da se ne koristi vise

Vremenske prognoze više ne komentiram.

nadam se,ali teško,RB uvijek nađe nekoliko desetinki više od svih ostalih i bez kersaelder je napisao/la:Red Bull za Kinu najvjerojatnije nece korisiti KERS, a s obzirom na dosta dugu ravninu mislim da bi im to mogel biti jako veliki hendikep.

http://www.autosport.com/news/report.php/id/90626" onclick="window.open(this.href);return false;

Malaysia GP Roundup: A Case Study On How To Dominate

April 12, 2011 - What we saw in Sepang, as in Melbourne, was a case study in how to win a motor race with the best car by beating (a) a very quick team-mate in both qualifying and the race; (b) teams like McLaren and Ferrari; and (c) drivers like Lewis Hamilton, Jenson Button and Fernando Alonso. A case study in how to dominate, in other words – dominate as Michael Schumacher or Niki Lauda used to dominate.

Crucial in 2011, with the reduction in tyre allocation (six sets in total by the time you get to qualifying) – the object is to use the absolute minimum number of Pirellis. One set (one quick lap) in Q1, one set in Q2 and two sets in Q3. Maximum. Make it work. Make it happen. It’s not enough just to “save” sets for Q3. It’s also about saving the number of laps on each set. The race, in 2011, starts in qualifying – with minimizing the usage of both prime and option tyre right from the start of Q1. The less you use them, the more you can race them.

Seb Vettel did exactly that, cruising through Q1 in Sepang on primes while thinking already of the Q3 lap. Both McLaren drivers, meanwhile, used two sets of primes. Seb was slower than both McLaren, Ferrari and Lotus Renault drivers, plus Kamui Kobayashi (Sauber) – but was through to Q2 with only three laps behind him. Only the Lotus Renault drivers matched that – and they were hardly shooting for the pole.

Q2, on options, was another success: Seb was third quickest (behind Lewis and Jenson) and fractionally quicker than Mark. Jenson had only one run but Lewis went for two – a choice that would affect him exponentially on Sunday. Total laps at this point: Seb six, Lewis 13, Webber 10, Button nine, Fernando 11. So Seb was doing more with less. It is the heart of what his 2011 is all about.

The pole, though, is the pole: you have to go for it. This year at Sepang, following discussions about the left (or “clean”) side of the road being so open to inside passes into Turns One and Two, it was decided that the pole would be on the right. That being so, McLaren’s hand was strengthened slightly: their engine and KERS hybrid performance is unsurpassed in F1 and a Lewis on the inside pole, even with a slowish start, would still probably retain the lead into T1. A Lewis from the outside pole, again with a mediocre start, would not necessarily be able to lead the pack into T1 – or out of T2, let’s put it that way.

Ergo, it was crucial to out-qualify Lewis – partly because it’s always better to be in front and partly because it would nullify the effect of the new pole side if things went wrong.

Lewis was slightly quicker on his first run – 1min 35.0sec to 1min 35.1sec. He had done more laps. He knew the limit of the McLaren; he knew from where the option grip would come. Webber was 0.1sec slower again.

And so to the final, dying minutes. Seb sat and waited, sat and waited, staring at the timing monitor but thinking still of the lap. McLaren were back out. Ferrari too. And Webber. Fans and flexi-ducts blew cool air into his face, through the helmet opening. Mechanics stood by, patting their brows with paper wipes. And now, finally, they lowered his car and peeled off the tyre warmers. He eased the hand clutch and drove hard right into the pit lane, shutting his visor as he did so.

A slow out-lap – but not too slow. Start to lean on the tyres a little in the second half of the lap. Brake early for T15. Nice, clean exit. KERS! Go! As Seb crossed the timing line there were but 12 seconds of Q3 still to run.

It was a classic Seb lap – of the type we saw in Melbourne and at many other tracks in 2009-10. Lots of microscopically small foot and hand movements, all of which added up to a smooth-looking lap that the media would describe simply as “easy” or “relaxed”. Lots of inputs – and lots of platform around which to manage those inputs. No “moments”. No dashes for the line. No locked inside fronts. No loaded rear “bobbles” on the kerbs. Just a lap about as perfect as one can be driven in this car, on these tyres, on this day.

Thirty seconds before the chequered flag, Lewis became the first driver to break the 1min 35 sec barrier. 1min 34.974 sec! Faces lit up in the McLaren garage. The world TV feed was unaccountably showing only Fernando and Jenson with a little bit of last-minute Lewis. Webber crossed the line. 1min 35.179. Where was Seb?

Seb was sculpting it out. He exited the last corner, RBR7 perfectly-positioned. Hard acceleration, keeping the car tucked to the right, absolutely straight. 1min 34. 870 sec! The Sepang pole was his.

You don’t get too carried away; you don’t do anything that you wouldn’t do normally, even though you’ve won the World Championship and you’ve won again the pole – won it against drivers like Lewis and Mark. You are polite and you talk to every journalist who asks a question. And then you thank the team and sit down with them to digest.

The big issue, pre-race, was of course to do with KERS. It’s one thing to say that it’s 80 extra horsepower; it’s another to be able to use that extra bhp without ruining the handling balance or putting so much energy through the rear tyres that it compromises their life. It was obvious that RBR had to use KERS off the line in Sepang – they would be swamped if they did not – but what would be its advantage vs disadvantages in the race that followed? For all its power and its so-called benefits, it is a complex, complicated addition that can go wrong at any moment, particularly in a car that is as tightly-packaged as the RBR7. Indeed, Mark’s KERS system proved tetchy in qualifying – so much so that it was moved away a little from the other cars in Parc Ferme because of the potential for some sort of electricity-related drama.

Clouds loomed as the 16:00 start time drew near but the word on the grid was that rain, if it came, was at least 30 min away. Seb accelerated away cleanly but Lewis, as expected, quickly narrowed the gap. Seb perfectly used his mirrors and his body language to shut down any discussion about the first corner – but it was a closely-run thing. Had the pole been on the left, and had Seb and Lewis made the same starts as they did in reality, Lewis would possibly have had a very clear run into the Turn 1 apex. As it was, he queued up behind Seb and suddenly found Nick Heidfeld on his outside. And if you’re on the outside of T1 at Sepang you’re on the inside for T2. Lewis had to back away and lose position.

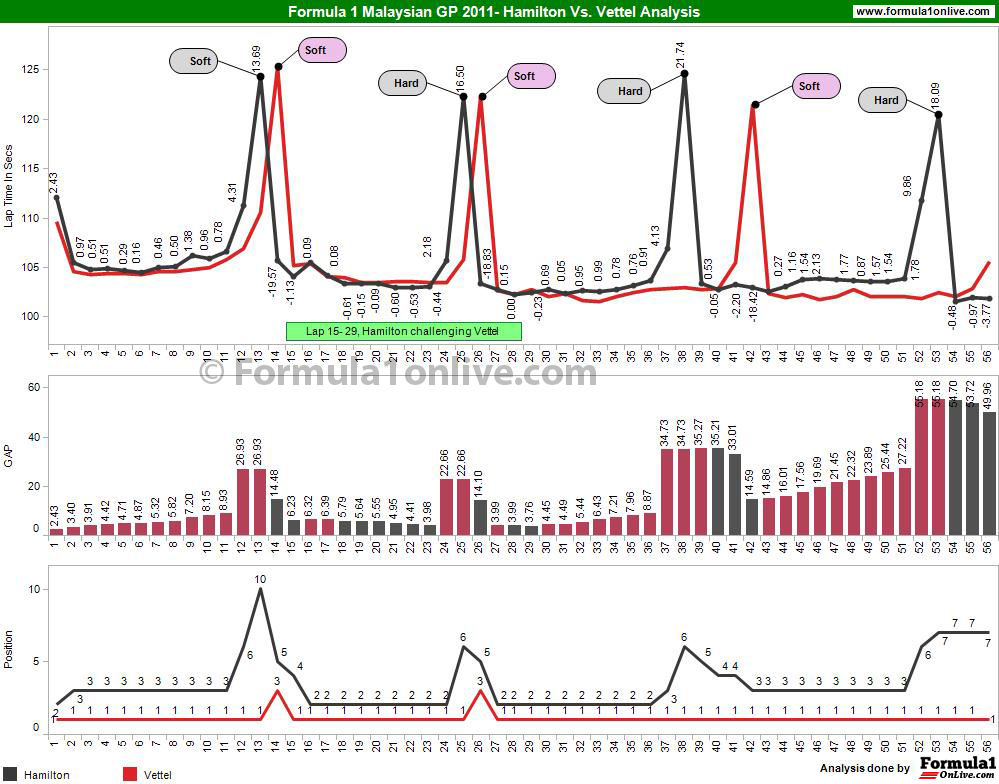

Which gave Seb the race, in effect. He could peel away from Nick virtually as he chose – and he chose to do so with discretion, watching his tyres and using his KERS with caution. The only tense moments came just before mid-race, when he was advised not to use his KERS system at all. Mark had indeed had a further problem off the line, swamping him down to the mid-field, and thoughts of rock-solid reliability now ruled the RBR pit-wall. On hearing the news, you could almost see the relief in Seb’s track language. Driving the RBR7 in harmony with the road, the tyres and the fuel load, and not relying upon an artificial boost perhaps to make up for some other shortcoming, Seb at this point began to pull away from the McLarens, demoralizing them totally. A radio message exhorted Jenson to “get near to Vettel if you can; he’s got a KERS problem” – but Jenson could do nothing about it. Without KERS, the Red Bull and Vettel was a McLaren-beating package. Seb maximised the tyre advantage he had earned in qualifying. He sat squarely in the middle of Adrian Newey’s sweet spot, massaging the maximum from his tyres in all four stints. Lewis, carrying those extra q-laps into the race, would eventually stop four times, although he would lose track position to Jenson after a slow pit stop three. (Bear in mind that there were 63 pit stops in this year’s Malaysian GP, and that a team like McLaren is called to do seven of them, all under four seconds, and it’s no surprise that the errors creep in. Jenson, who had started with a four-lap tyre advantage over Lewis, finished a valiant, three-stop second.

The minor placings also brought out some majorly good drives. Nick Heidfeld’s speed and consistency resulted in third place for Lotus Renault – a result that must again remind us of poor Robert Kubica, trapped back in Europe as he is, knowing how good his season would now have been. Renault had a tough start to the weekend, with the front uprights on both cars failing on Friday (due to a specific batch of duff material) but recovered beautifully – just as they always used to in the old days of Pat Symonds, Bob Bell and Flavio. The new regime, under Eric Boullier, Alan Permayne, James Allison and Steve Nielsen, are no less efficient. Webber fought hard to finish fourth (there was little talk in Malaysia of any “mechanical” issues that might have hurt his performance in Australia) and the Ferraris finished fifth and sixth, ahead of Lewis Hamilton – before, and after, time penalties.

After a gritty drive through the first two phases of the race, Fernando, whose adjustable rear wing was not working, could have been fourth for Ferrari in Malaysia, maybe third. With ten laps to run, however, he classically mis-judged a pass on Hamilton as they accelerated out of the T3 kink, when Lewis’s tyres were shot (again). Fernando ran much too closely to Lewis’s right rear, caught some understeer, and plucked away the Ferrari’s left-front wing. It could have been a huge accident; it was an error that a driver of Alonso’s quality should not have made. The FIA Stewards oddly decided to penalize both drivers after the race but to my mind this error was all Fernando’s. The Stewards have subsequently pointed out that the penalty for Lewis was for some steering wheel movement he gave the car the lap before he was hit from behind. If so, it’s strange that Fernando admitted afterwards that the two of them had to “race hard” and that Lewis “defended very well” – and that if anyone was going to be critical of some movement not shown on the general TV feed then it is Fernando. Would the Stewards have penalised Lewis if Fernando had not hit him? Personally I think not. In any event, penalising Lewis after an incident like this can only send out the wrong messages to everyone – young drivers and current ones – particularly if it clouds the real mistake at hand – Fernando Alonso’s mis-judgement. For his part, Lewis accepted the penalty with good grace – but what choice did he have? I later watched a replay of the race and counted no fewer than eight drivers (including Seb Vettel on the first lap) who moved the steering on the straight just as much as did Lewis and yet received no penalty at all. It is the inconsistency that is the disturbing thing here – the inconsistency and the suspicion that Lewis receives far more than his fair share of penalties.

No-one begrudged Kamui Kobayashi and the Sauber team a seventh place (nee eighth place) finish in the points (ahead of Michael Schumacher’s Mercedes and the equally-impressive Paul di Resta, who again beat his Force India team-mate, Adrian Sutil). Of course Sauber’s “illegal” rear wing in Australia gave no material advantage – and here was the proof. Kamui worked hard to cure a wayward rear end in practice (well, reasonably hard: Kamui isn’t averse to bouts of high-speed oversteer, particularly under braking. These are the moments he kind of lives for!) and he was a model of controlled, aggressive consistency throughout the race, using (as is Sauber’s wont) a lean, two-stop strategy to race closely on occasions with the likes of Mark and Michael.

Sixty-three pit stops – but, in reality, it wasn’t these that defined the race: it was qualifying. Tyre usage in qualifying. Getting the best from the tyres and the car with the minimum of laps. Squeezing more from less. Timing it perfectly.

As exemplified by a 23-year-old German named Sebastian Vettel, who, on this hot and humid Malaysian day, justifiably scored career win number 12 and reminded us not a little of some other great drivers – of when they were dominating, too.

The Petronas Malaysia GP, Dan Gurney and the upcoming UBS Chinese Grand Prix will be the main topics of discussion on this week’s ’The Flying Lap with Peter Windsor’, Episode 15.